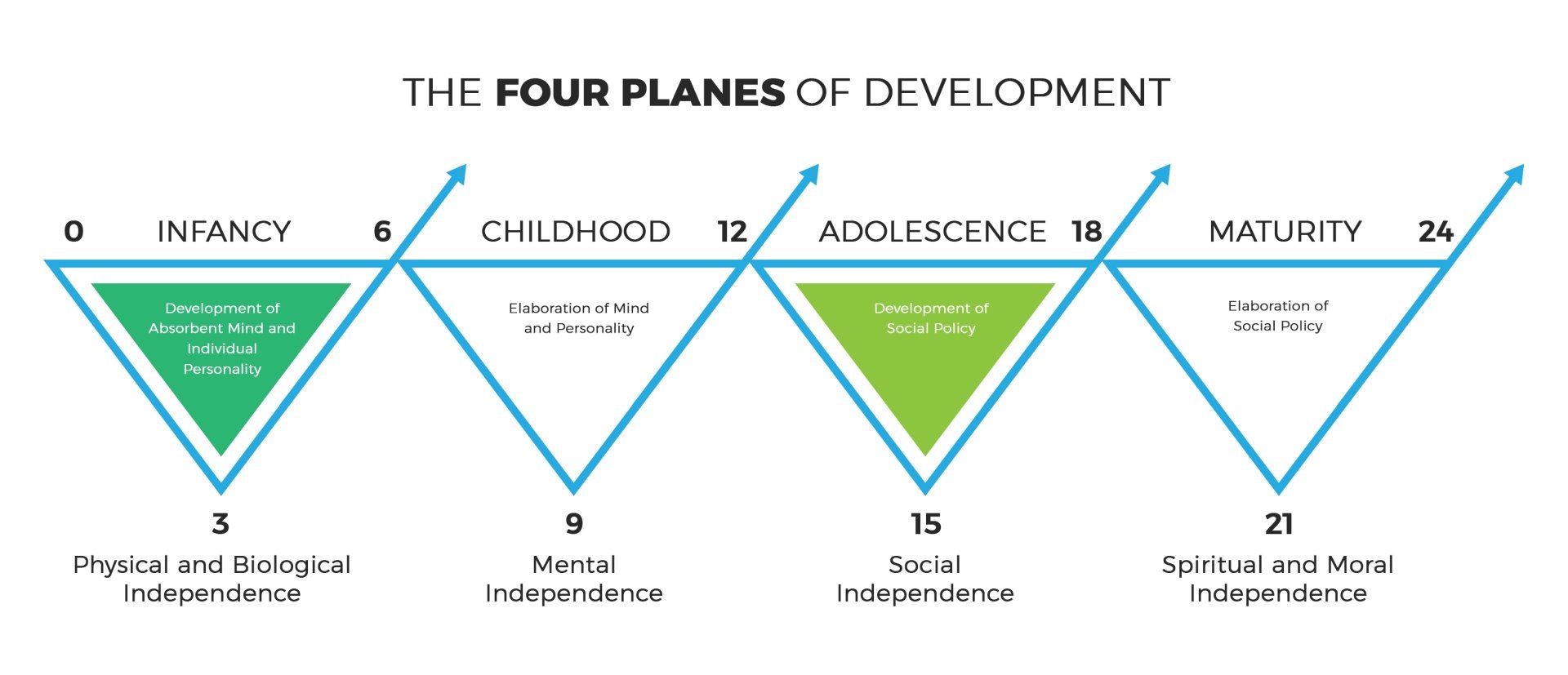

Maria Montessori based her entire educational philosophy on the idea that children developed through a series of four planes. Each of these planes is easy to recognize and has clear, defining characteristics. If we study and understand these stages, we can approach our interactions with children with a new perspective.

Learning about the planes of development isn’t just for Montessori educators. Understanding your child’s development can help at home, too.

The First Plane: birth-6 years

During this stage children absorb everything like sponges. They are, indeed, excellent examples if what Montessori called ‘The Absorbent Mind.’ This is a time in which we are able to utilize what Montessori called sensitive periods of learning. While each child is different, there are typical patterns that emerge in regards to brain development and general readiness to learn particular skills.

During the first three years of this plane, all learning is done outside of the child’s conscious mind. They learn by exploring their senses and interacting with their environment. During the second half of the plane, from about 3-6 years, children enter the conscious stage of learning. They learn by using their hands, and specialized materials in the Montessori classroom were developed with this consideration.

During this time, children have a wonderful sense of order. They are methodical and can appreciate the many steps involved in practical life lessons in their classrooms. The organization of the works on their classroom shelves is intentional, which appeals again to this sense of order.

The first plane is a time in which children proclaim, “I can do it myself”; it is a time of physical independence.

The Second Plane: 6-12 years

During the elementary years children begin to look outside themselves. They suddenly develop a strong desire to form peer groups. Previously, during the first plane, a child would be content to focus on their own work while sitting near others. In the second plane, a child is compelled to actually work with their friends. It is during this time that children are ready to learn about collaboration.

During the second plane there is a sudden and marked period of physical growth. This may be a contributing factor to the observation that many children of this age seem to lack an awareness of their body, often bumping into things and knocking things over. Children begin to lose their teeth around this time as well. Their sense of order and neatness tend to fade a bit during this plane.

Throughout the second plane, children’s imaginations are ignited. Since Montessori education is based in reality, we find ways to deliver real information to children through storytelling and other similar methods. For example, when teaching children about the beginnings of our universe, Montessori schools use what is called a Great Lesson. The first Great Lesson is a dramatic story, told to children with the use of props, experiments, and dramatics (think: a black balloon filled with glitter is popped to illustrate the Big Bang, with bits of paper in a dish of water used while talking about particles gathering together). This lesson is fascinating for children in the way it is presented, but gives them basic information about the solar system, states of matter, and other important concepts.

Children in the second plane have a voracious appetite for information, and are often drawn strongly to what we in Montessori call the cultural subjects: science, history, and geography. While we support their rapid language and mathematical growth during this time, we are also responsible for providing them with a variety of rich cultural lessons and experiences.

It is important to note that children develop a sense of moral justice at this time. They are very concerned with what is fair, and creating the rules to a new game is often as important (if not more so) than playing the actual game itself.

This is the period of time in which children are striving for intellectual independence.

The Third Plane: 12-18

The third plane of development encompasses the adolescent years. During the second plane, children become aware of social connections, but in the third plane they are critical. During this time children rely heavily on their relationships with their peers. They feel a strong desire to remain independent from adults, although they are not quite ready to do this entirely. It is our job to find ways that allow them to experiment with independence while also providing a safe structure in which they may do so.

Children in the third plane tend to require more sleep, and they sleep later than when they were younger. They long for authentic learning experiences, and Dr. Montessori imagined just that. Her ideas of Erdkinder (children of the earth) led her to contemplate a school setting that would support children’s development during this time. She imagined a farm school, in which children would work to keep the farm operational, but also contribute to planning and decision making while doing so.

During the third plane children are refining their moral compass while developing a stronger sense of responsibility.

The Fourth Plane: 18-24

The final plane is a time in which young adults are striving for financial independence. They are often living away from home for the first time, and use this time to figure out where they fit into their society. Many make choices to further their education and/or explore career paths.

It is during the fourth plane that people begin to develop a truer sense of who they are as individuals.

Each plane of development should be mindfully nurtured. If a child is able to experience one developmental phase in a rich and carefully prepared environment, they are ready to fully take on the next phase when it is time.